Adam Rowe

Lead Designer

The deep meaning behind three simple numbers

October 16, 2020—Product development in an enterprise organization is a complex prospect, consisting of many moving parts that require coordination and alignment between people spread across the company. Successful product development depends on a stable foundation, but it must also be able to adapt to the ever-evolving needs of customers.

To drive efficiency and cohesion across products, large organizations build shared tools and services that product teams can leverage: the Morningstar Design System is a perfect example of such a tool. However, shared tools must be managed carefully to ensure that as they are updated, consumers can adopt those changes with as little friction as possible. How can product teams balance this agility with a need for stability?

Thankfully, modern software development practices equip us with a convention to quickly communicate the ways code has changed from version to version: Semantic versioning.

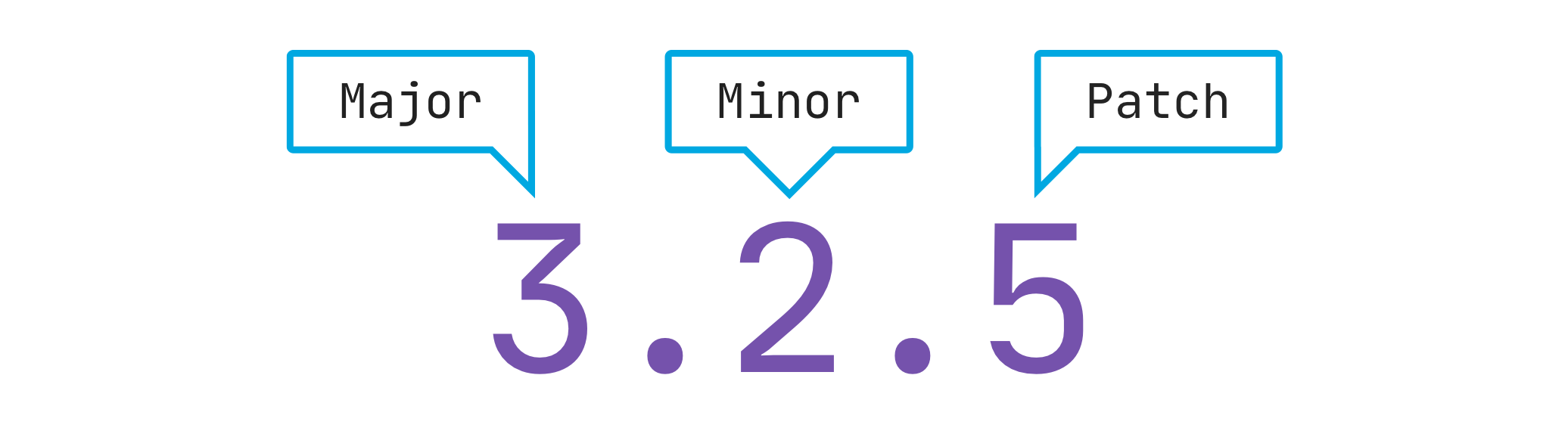

Semantic versioning—or SemVer, as its often referred to—is a standard that applies very specific meaning to a software’s version number. Most of us will be familiar with the presentation of a version in software or a mobile application, which is usually represented by three numbers, for example, 3.2.5.

Using SemVer, we can extrapolate complex meaning out of these three simple numbers. Let’s break down exactly what they mean:

The first number represents the major version, the second is the minor version, and the third is the patch version. Using our example above—3.2.5—we can quickly tell this piece of code is on its third major version, second minor version, and fifth patch version. These three different versions have very specific meanings which are used to communicate the types of changes to the code.

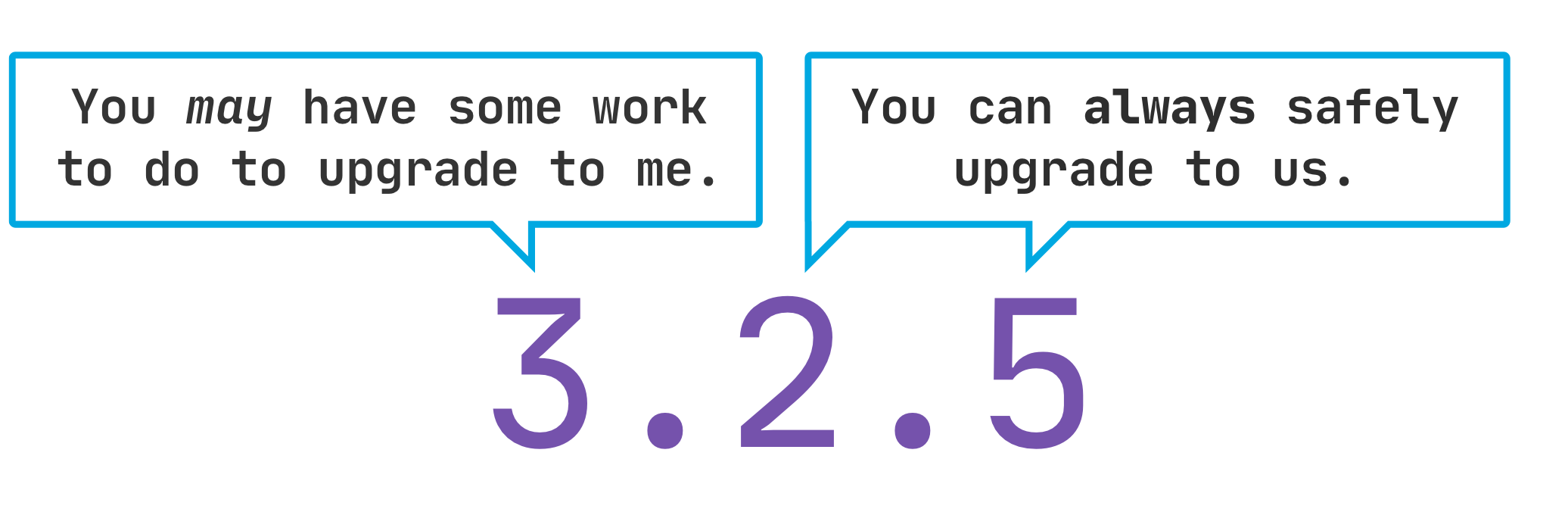

Major changes usually consist of big changes like redesigning a component to improve the user experience. While clearly beneficial, these changes also come with a cost, because they may involve significant changes to the way a component’s code is written, and may not be backwards compatible, requiring a consuming application to update their code. For these reasons, major versions are the least common type of change.

Minor versions indicate that something new has been added to the code, for example, a new optional feature. Minor versions are always backwards compatible, which means that all existing functionality will work the same as before, and no action is required by the consuming application.

Like minor versions, patch versions are always completely backwards compatible. Rather than new features, however, patch versions usually consist of bug fixes or other changes to the code that require no action from consuming applications.

On the MDS team, we value our relationships with our customers above all else. Trust is a key aspect of the bonds that we have built with Morningstar product teams over the last four years.

In practice, this trust means that our customers know that when we release a new version of a component, we are taking the utmost care to ensure that the updates we make won’t break anything that they are doing today.

By adhering to SemVer, we can clearly communicate the types of changes in each new version, allowing product teams to upgrade components with a clear understanding of what is included and if any work will be required on their part.

Minor and patch updates to MDS components will always be completely backwards compatible, which means that teams can pull in those updates without fear of introducing any issues.

Minor and patch updates to MDS components will always be completely backwards compatible, which means that teams can pull in those updates without fear of introducing any issues.

Major versions may not be backwards compatible and may include breaking changes that require refactoring to take advantage of improvements or new capabilities. Major versions will always be accompanied by documentation on what changed and how teams may need to adjust to ensure compatibility with the new version.

On the MDS site, you can find documentation on how we assign versions - including the specific criteria we use to determine if a change is a patch, minor, or major update.

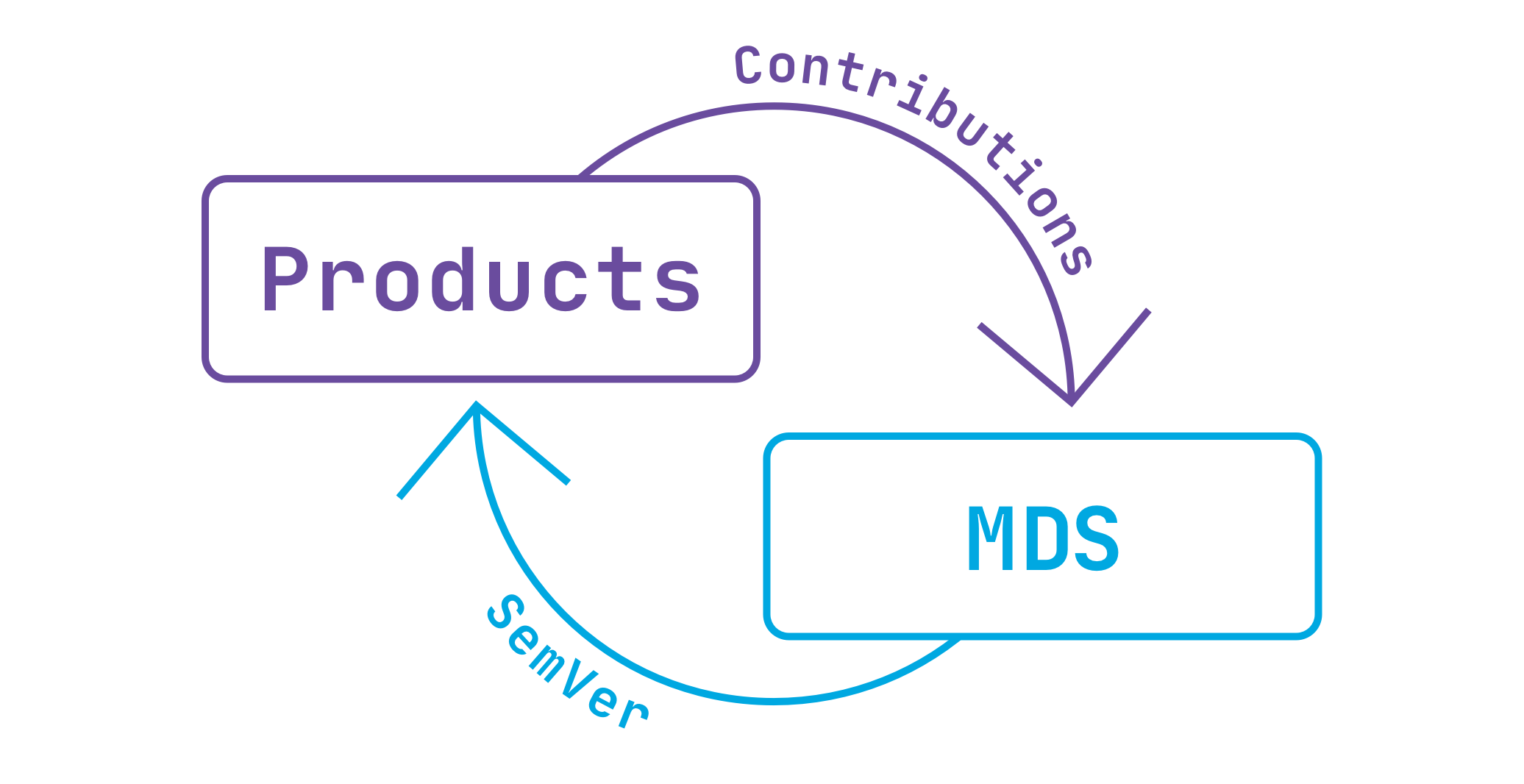

Since minor and patch versions will always be backwards compatible, product teams can configure their MDS dependencies to automatically pull in all patch and minor updates. In practice, this simply requires dependencies on MDS components to use the ^ operator in their package.json, the file that manages all the dependencies consumed by a product.

From that point forward, whenever a product team upgrades their MDS dependencies they will automatically pull in all minor and patch versions. This ensures that our customers will always have access to all bug fixes and new features.

This tight coupling between MDS and our customers also drives community contributions and ensures we are developing a communal system. Teams that are set up to automatically pull in updates to MDS have extra incentive to contribute fixes and enhancements back to the system, since they will be able to immediately consume those contributions in their product.

In product development, the term “breaking change” is one that may elicit some anxiety. In fact, in previous versions of MDS each major version included a long list of changes with potential to impact existing implementations. This created challenges for product teams who had to assess the impact of all changes and then plan and prioritize the work required.

As we wrote about in a previous post, this all changed with our move to a componentized architecture. By packaging each component individually, we can make major updates to components without impacting the rest of the library. And even major updates will often require no action from consuming applications. Just because a change might be breaking, doesn’t mean it will be for your use case.

This doesn’t mean that we take major versions lightly, but it does equip us to continue iterating and improving our components to meet our customer’s needs. It means that we can act on good ideas, pivot to meet new challenges, and continuously improve, even if doing so would require breaking changes and new major versions.

Semantic versioning allows us to act on good ideas, pivot to meet new challenges, and continuously improve, even if doing so would require breaking changes and new major versions.

While they shouldn’t happen frequently, new major versions of components are a clear indication that MDS is continuing to improve, and always striving to provide both Morningstar product teams and our customers with the delightful, intuitive experiences that Morningstar is known for.